In economic terms, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was not limited to health crisis; it triggered a global economic shock, drastically reducing demand, disrupting supply chains, and prompting governments to inject trillions into struggling economies in an effort to prevent collapse. Virtually overnight, the pandemic exposed the fragility of modern markets, leaving policymakers struggling to balance the collapse of aggregate demand with sudden disruptions in aggregate supply. Due to which it becomes important to understand COVID-19’s impact on aggregate supply and demand.

New estimates from the World Health Organization (WHO) show that the full death toll associated directly or indirectly with the COVID-19 pandemic between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2021 was approximately 14.9 million

Table of Contents

Purpose of this article:

This article is to understand the economic impact of the covid 19 pandemic on aggregate demand and supply of the economy, aiming to provide insights for readers and researchers interested in the economic recovery after COVID-19 and the forces driving it. It offers a simplified understanding of complex economic terms, making it accessible for those new to this field.

To enhance readability, especially for those new to economic terms, this section breaks down what is aggregate demand and aggregate supply. These concepts are essential for understanding an economy’s health and responses to major disruptions. Aggregate demand (AD) reflects the total demand for goods and services in an economy and plays a key role in driving employment, production, and inflation. When AD is strong, businesses produce more, leading to higher employment and economic growth. Conversely, a decline in AD can lead to a recession, as seen during COVID-19.

On the other hand, Aggregate supply (AS) represents the economy’s capacity to produce goods and services, which affects growth potential, inflation, and employment levels. What happened to aggregate supply during COVID was a series of global supply chain disruptions, labor shortages, and production slowdowns. When aggregate supply is unable to keep up with aggregate demand, inflation may rise as demand outpaces supply. Conversely, when AS expands, it can accommodate higher levels of demand without causing inflation, leading to sustainable economic growth. This topic has been widely studied in research papers on the COVID-19 impact on the economy, examining how these forces shape economic recovery strategies.

Aggregate Demand

The overall spending of goods and services by all sectors of an economy, be it household, government or foreign institutions, who are willing to purchase commodities at a given price level in a given period of time, is known as Aggregate Demand.

AD = C+I+G+NX

or AD = C+I+G+ (X-M)

Where, C is Consumption,

I is Investment,

G is Government spending,

and NX is net export, which is export (X) – Import (M)

Its Components are: –

- Consumption: It is the total spending by household on food, clothing, housing, healthcare and so on.

- Investment: It shows the business spending on factories, capital or new industries. It represents the future prospect also it is highly profit driven.

- Government expenditure: Expenditure made by government on public services like education, healthcare, or infrastructure. It is based on the concept of welfare.

- Net Export: It is the difference between countries export of goods and services to that of countries import.

NET EXPORT = Export – Import

Aggregate Supply

Aggregate Supply refers to the total quantity of goods and services that producers in an economy are willing and able to supply at a given overall price level over a certain period of time. It represents the economy’s production capacity and reflects the relationship between price levels and the output firms are ready to produce.

Types of Aggregate Supply

Aggregate supply can be understood in two timeframes:

- Short-Run Aggregate Supply (SRAS):

- In the short run, the quantity of goods and services supplied in the economy can increase as prices rise, while some input costs (like wages and raw materials) may remain fixed. This leads to upward-sloping short-run aggregate supply.

- In this period, businesses can adjust production by hiring more workers or utilizing existing capacity more intensively, but they cannot easily change factors like factory size or technology.

- Long-Run Aggregate Supply (LRAS):

- In the long run, aggregate supply is assumed to be vertical (perfectly inelastic), meaning that the economy produces its maximum potential output (or full employment output) regardless of the price level. This is because, in the long run, all prices, including wages and input costs, are fully flexible.

- LRAS depends on factors like the labor force, capital stock, technology, and natural resources, which determine an economy’s productive capacity.

Factors Influencing Aggregate Supply

Several factors affect aggregate supply in both the short and long run:

- Input Prices: In the short run, a decrease in wages or the cost of raw materials can lead to an increase in SRAS, as production becomes cheaper for firms.

- Productivity and Technology: Advances in technology or improvements in productivity allow firms to produce more with the same number of inputs, shifting AS to the right.

- Labor Supply: A larger labor force or higher skill levels increase the productive capacity of the economy, positively affecting both SRAS and LRAS.

- Capital Stock: An increase in physical capital (machinery, infrastructure, etc.) enhances an economy’s ability to produce more goods and services.

- Government Regulations and Taxes: Lower taxes and reduced regulations can decrease production costs, increasing AS. Conversely, increased taxes or stricter regulations can shift AS to the left.

- Expectations of Future Prices: If firms expect higher future prices, they may reduce supply in the short run to take advantage of future profits, lowering SRAS.

- Supply Shocks: Events such as natural disasters or geopolitical conflicts can cause sudden disruptions to production capacity, reducing aggregate supply.

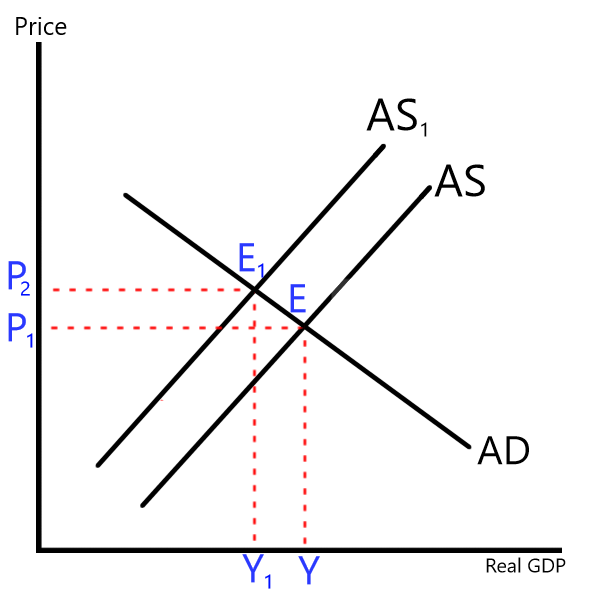

Understanding the case study with a graph

At this point, we’ve built a solid understanding of COVID-19’s impact on aggregate supply and demand and how the pandemic disrupted economic equilibrium. Before 2019, the economy was assumed to be in equilibrium at point E. However, when COVID-19 hit, the economy faced significant shifts, with a severe impact on aggregate supply. So, was COVID a demand or a supply shock? In reality, it was both, but the immediate effects were largely supply-side disruptions.

The pandemic caused a sharp reduction in the supply of goods for several reason:

1. Sudden changes in consumer’s demand. People began to prioritize essential goods such as food, surgical masks and so on, out of which demand and supply of hand sanitizer during covid 19 increases abruptly.

2. Disruption in logistics was another major issue, orders were getting delayed for even more than a month. This is how covid affected supply chain which led to further shortages.

3. Poor health of workers who begin to come in the trap of the pandemic, as a result reducing production capacity.

And these factors led in increasing the cost of production or input cost, causing the aggregate supply curve to shift leftward. As a result, the quantity of goods supplied decreased, moving the economy to a new equilibrium, E1. Where price was increased to P2 from P1 and the real GDP of an economy decreases from Y to Y1.

This new equilibrium at E1 created a situation of stagflation- a rare and challenging economic condition where the economy experiences stagnant growth, high unemployment, and rising prices all at once. Stagflation is particularly hard to manage, as addressing one issue can exacerbate others. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) highlighted in a press release that stagflation risks spiked during crises such as the Asian Crisis, the Global Financial Crisis, and the COVID-19 pandemic. However, as of Q2:2023-24, the likelihood of stagflation in India remains very low, at only 1% (source: RBI Press Release)

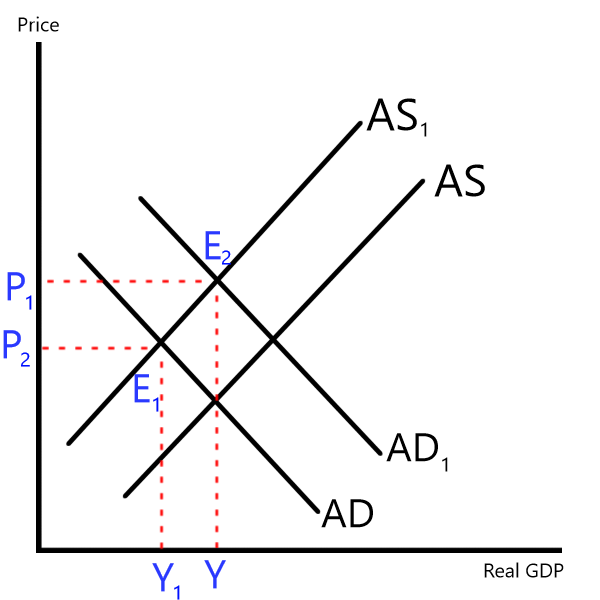

To address the economic downturn and maintain consumption, the Government of India took several steps: it provided food packages, transferring the cash directly to the accounts of vulnerable sections, and several stimulus packages across various sectors. All this was done to maintain the level of consumption in the economy, in order to support businesses, strengthening healthcare and boosting employment.

Consequently, aggregate demand began to increase, shifting the demand curve rightward from AD to AD1. The new equilibrium, E2, saw prices increasing again, but this time with an increase in real GDP from Y1 to Y2, indicating a gradual recovery in economic activity.

As demand rises, however, a crowding-out effect may occur, potentially discouraging private investment. To counteract this, the RBI can use tools such as monetizing the deficit. This process, sometimes referred to as money market regulation, aims to mitigate the crowding-out effect. By increasing the money supply- either through open market operations or printing new currency- the RBI can reduce interest rates, encouraging private investment, which in turn increases aggregate demand and ultimately real income.

We will delve further into these dynamics in another article, examining the data and effects in detail.

Conclusion

In summary, COVID-19’s impact on aggregate supply and demand exposed significant vulnerabilities in the global economy, shifting both supply and demand in unprecedented ways. The pandemic triggered a dual shock: supply chains were disrupted, consumer behaviors changed, and many sectors faced reduced workforce capacity. This led to a stagflationary environment with high unemployment, rising prices, and slow growth.

However, efforts toward economic recovery after COVID-19 were initiated through a range of policy interventions, including government stimulus measures, direct support to vulnerable populations, adjustments in monetary policy by institutions like the RBI. These actions have helped stimulate aggregate demand and gradually move economies closer to pre-pandemic activity levels.

The impact of COVID-19 on the global economy will continue to inform future economic policies. As countries strive for resilience, learning from these experiences can aid in building stronger, more adaptable economies capable of managing future crises more effectively.